2021A la UneNotes et baromètresPublications

Production Taxes Hold Back Wages, Jobs and Growth

Read the study (PDF Format)

Read the Press release

Lire l’étude en français (Format PDF)

Lire le communiqué de presse

SYNOPSIS OF THE STUDY

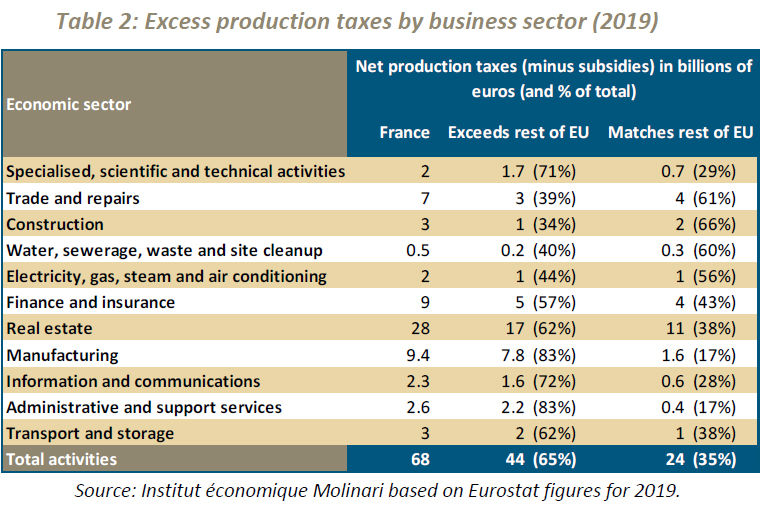

- Bringing French taxation in line with the European level involves reducing production taxes by at least €45 billion (considered in terms of GDP, with production subsidies deducted).

- In comparison, the reduction enacted by the government as part of its recovery plan is limited to €10 billion.

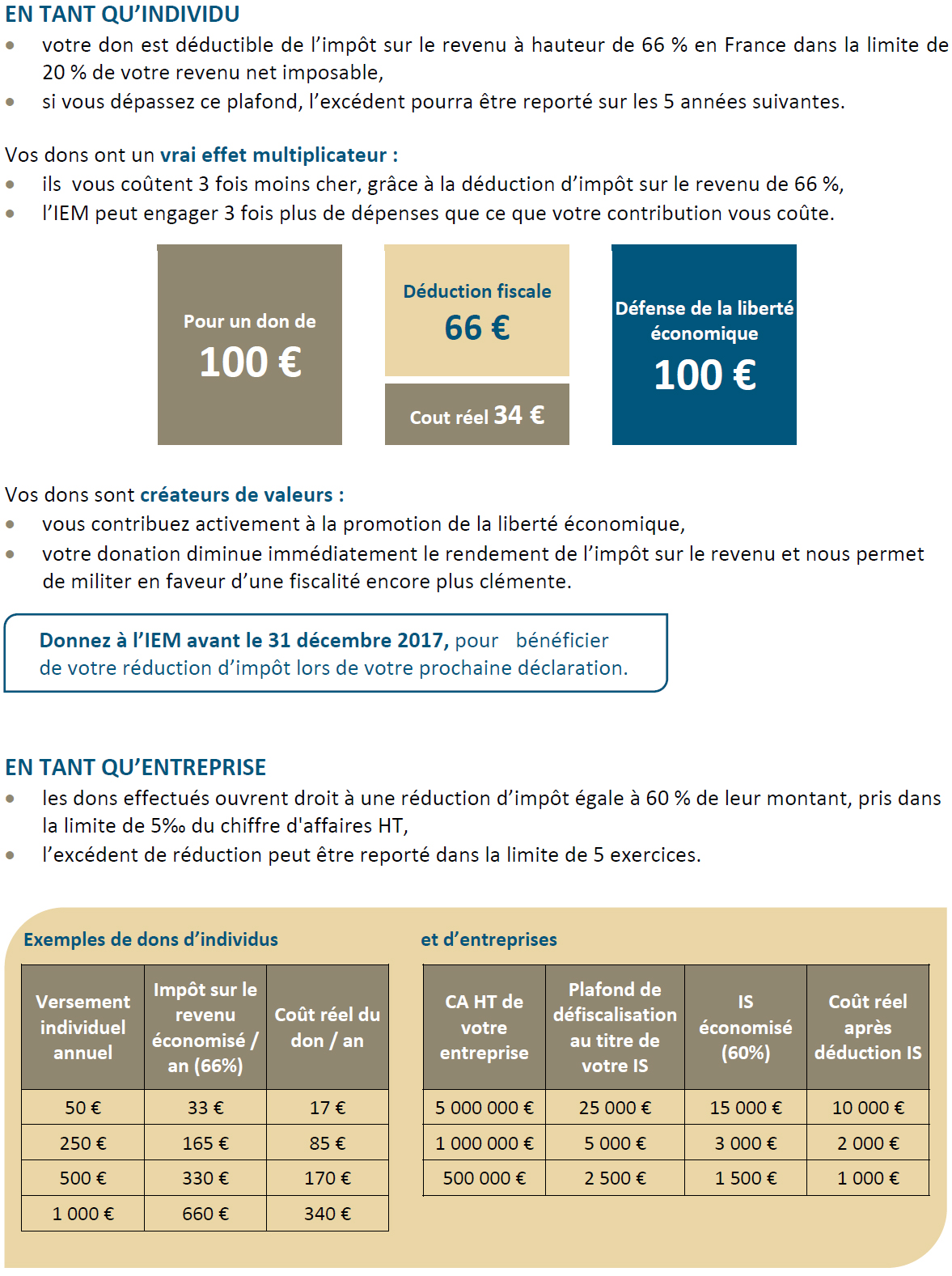

- An additional €35-billion reduction in production taxes would generate win-win rippled effects for French society, with €156 billion in additional turnover and €12 billion in net surpluses for companies.

- Members of the workforce, whether employed or unemployed, along with their social security programs, would come out on top, with €42 billion in additional pay (including €25 billion in net wages) and the creation of 750,000 jobs.

- Public finances would not be destabilised: production taxes could be reduced without raising other forms of taxation or adding to public deficits. The decline in production taxes would be offset within two years by increases in social contributions (+€17 billion), corporate tax (+€7 billion), personal income tax (+€2 billion) and VAT (+€1 billion) along with a decline in unemployment-related expenditures (+€11 billion).

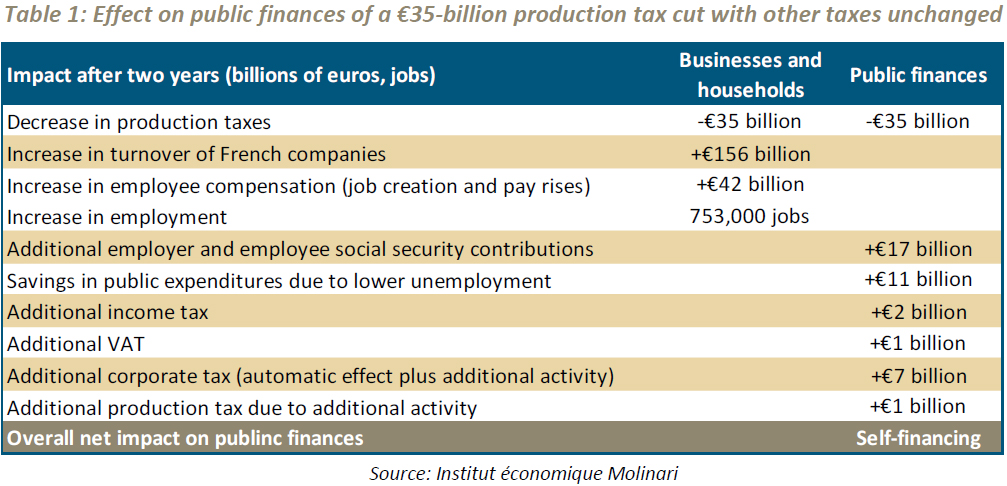

- Comparisons show that the French economy is suffering from a level of production taxes that is out of line with the country’s value added. France accounted for 33% of net production taxes in the EU 28 but only 15% of value added in 2019.

- In some business sectors, three-quarters of production taxes would have to be eliminated to move into alignment with the added value generated. This applies especially to information and communications, administrative and support services, and transport and storage. In industry, the cuts would have to go even further, with four-fifths of production taxes eliminated.

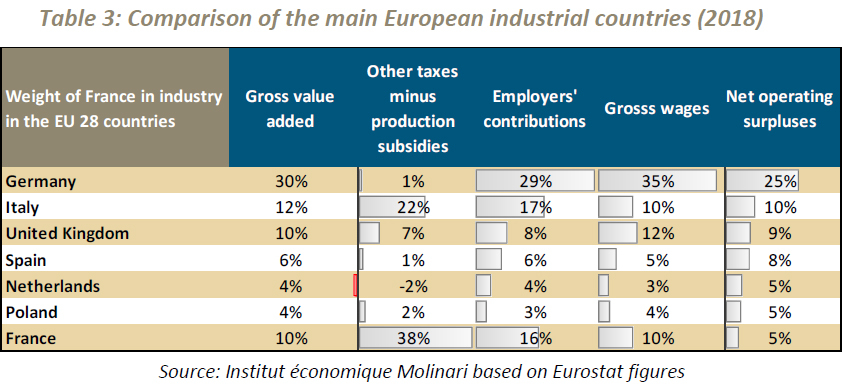

- French industry is penalised by production taxes that account for 38% of the European Union total even though it produces only 10% of value added. Production taxes and, to a lesser degree, employers’ contributions, explain its lack of competitiveness, with gross wages not at issue.

- Production taxes are detached from companies’ performance or financial health and imperil the survival of low-margin French businesses, as shown by the recent closing of the Bridgestone tyre factory in Béthune. With €7 million in production taxes in 2018, this venture could not operate at a profit in France. It was losing €5 million a year due to the severity of French taxation. With various other industrial sites under threat (including plants run by Alcatel-Lucent, Jacob-Delafon, Michelin, Schneider Electric and Verallia), maintaining this form of taxation, which was supposed to be eliminated with the advent of the VAT in the 1950s, is simply nonsensical.

- An analysis of the burden of production taxes shows that it is ultimately borne by consumers, shareholders and employees. This burden is split in proportions that depend on the respective power of the various players. In areas exposed to significant international competition, there is little impact on consumers who have access to foreign products that incorporate lower levels of taxation. The tax burden then falls on shareholders and employees, based on variable time factors. Shareholders, with less mobility in the short term, are likely at the outset to assume a significant portion of production taxes. But they remain mobile in the long term and can cut back on investments in countries with more highly developed taxation, or they can simply pull out. Members of the workforce, whether employed or unemployed, are often the least mobile in the long term. They will bear most of the brunt of production taxes in the form of lower wages or lower employment rates.

- Local authorities will have to be compensated for shortfalls. They receive 66% of production tax revenues, and this accounts for 28% of their funding. The most promising solution is the sharing of traditional forms of taxation, as is done in many countries with consumption taxes (Canada, Spain and the United States), personal income tax (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) or corporate tax (Germany).