Tax incidence cannot be brushed aside

The concept – How it shows up in the digit tax, which taxes consumers rather than Big Tech

Who ends up paying compulsory levies, and which ones? For the general public, the answer is often simple and may depend on the name given to a tax. Companies supposedly pay the taxes that target them specifically (employers’ contributions, taxes on profits, etc.). Likewise, households pay the taxes applying to them (deductions from wages, income tax, VAT, etc.).

In reality, economic analysis shows that things are not nearly so simple. Households also pay taxes that are not directly aimed at them. By extension, they end up as the true payers of taxes on products, production or corporate profits. Unless this reality is properly taken into account in France, it causes misperceptions to proliferate, as shown by the emblematic case of the digital tax.

Centuries ago, economists noted that taxation is porous, moving from one player to another. They showed early on that the “statutory” or “legal’ taxpayer is not necessarily the one who actually pays the tax. The true tax incidence in fact depends on taxpayers’ ability to shift the tax burden onto third parties by becoming collectors of taxes paid by others. This “recognition that the burden of taxes is not necessarily borne by those upon whom they are levied” even constitutes, according to Kotlikoff and Summers, a “distinctive contribution of economic analysis”.[1]

Herein lies the interest in developing the analysis of tax incidence to determine who ultimately bears the burden of compulsory levies, regardless of who is involved in their collection.

SHIFTING TAXES ONTO CONSUMERS

Back in 1776, Adam Smith noted that many taxes “are not finally paid from the fund, or source of revenue, upon which it was intended they should fall.”[2] Often, the “tax is finally paid by the last purchaser or consumer.”[3] In 1817, David Ricardo stated that a “tax on raw produce would not be paid by the landlord; it would not be paid by the farmer; but it would be paid, in an increased price, by the consumer.”[4] In the late 1820s, French industrialist and economist Jean-Baptiste Say affirmed that “any tax is a burden that the taxpayer seeks to pass on to other members of society.”[5] He went on to state that “the tax that the producer is obliged to pay is part of his production costs. (…) He must increase the price of his products and in this way pass at least a part of the tax to his consumers.”[6]

From an economic standpoint, a tax burden falls all the more heavily on a factor inasmuch as it is “inelastic”. The ability to shift the tax burden to consumers depends on price elasticity.[7] The producers or distributors of a good in especially high demand, such as petrol, will be able to shift the economic burden of a tax increase onto their customers.

On the other hand, producers of goods in low demand will be less able to shift tax increases onto their customers. In the worst case, they will be forced to absorb the entire tax and to reduce their margins. This will result in a coincidence between producers subject to a tax (from a statutory or legal standpoint) and payers (from an economic standpoint).

Depending on elasticity of supply, taxation will lead to a fairly significant change in supply and/or demand. It will also reduce the quantities traded and diminish the usefulness of players, taking the form of a dead loss for society.

However, the reasoning does not end there, because analysis of tax incidence shows that a company unable to shift a tax onto its customers may also turn to its employees or shareholders. Companies penalised by the development of taxation will tend to be less generous when it comes to raising salaries or paying dividends to shareholders.

SHIFTING TAXES TO EMPLOYEES AND SHAREHOLDERS

The tax burden always ends up being borne by physical persons who are “owners of capital, employees and/or consumers”.[8]

Depending on the case, tax incidence ultimately rests upon consumers, employees, shareholders, business partners’ employees or shareholders, or employees or shareholders of business partners of companies in contact with the partners.

Once again, elasticity will come into play. The adjustments will depend on the sensitivity of capital and labour to the effective rate of taxation, just as they would with consumption.[9]

Economists agree that taxation affects the structures and factors that are least responsive and that have the fewest alternatives, in line with Maurice Lauré’s intuition that “the repercussions go from the economically strong to the economically weak.”[10] Simula and Trannoy note that “the flight movement of mobile factors

enables them partially to escape the tax and thereby to divert the burden of the tax onto other factors,”[11] while the least mobile factor cannot escape the tax. Of course, “the variation in prices caused by the variation in taxes leads to a change in the distribution of income, profits and well-being,” which, in their view, is “the ultimate purpose of tax incidence.”[12]

Hence the importance of moving beyond the legal constructs that Yuval Noah Harari, the author of Sapiens, rightly calls “social fictions” and of looking into the interactions in wealth creation and taxation.

A MAJOR TOPIC ENCOMPASSING TAXES ON PRODUCTS, PRODUCTION AND PROFITS

Contrary to a common belief, producers do not pass along taxation only on products. Their capacity for development often depends on shifting taxation on production tools and profits as well. Works by Arnold Harberger show, for example, that the corporate income tax penalises consumers, shareholders and employees in varying proportions, depending on the nature of the markets.[13]

In this process, there is reason to fear that certain companies, unable to shift tax incidence onto their employees, customers or shareholders, will be hindered in their development or may even disappear.

CASE-BY-CASE ANALYSIS IS NECESSARY

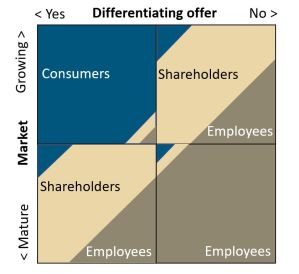

Further complexity arises from the great variation in the incidence of different taxes, depending on whether a business is on the upswing or downswing. In the former case, producers can easily transfer the burden onto buyers or consumers, while in the latter case they are obliged to bear it themselves, in whole or in part.[14] This is what led Maurice Lauré to say that examining incidences is possible only if the economic circumstances are known.[15]

Breakdown of tax incidence between players based on

the nature of offerings and markets

Reading: A player with a differentiating offer in a growing market will have no difficulty shifting tax incidence onto consumers. Conversely, a player with an undifferentiated offer will be unable to shift taxes onto consumers, will have trouble shifting taxes onto shareholders because of the mobility of capital and will tend to shift the burden onto employees.

TAX INCIDENCE, A BLIND SPOT IN FRENCH PUBLIC POLICY AND DEBATE

Unless this crucial tax and regulatory aspect is properly taken into account, many public policies are likely to miss their targets and/or to produce undesired or even adverse effects.

If tax incidence were more fully taken into account, France would in all probability have avoided ranking highest in business-targeted taxation, with oversized productions taxes and with corporate income taxes that exceed the European average. These taxes are often presented as proof of “social justice” and balancing of effort, with companies called upon to contribute as much as households, if not more. In reality, this is misleading. High taxes channelled through businesses necessarily fall on households. Though they may penalise shareholders, by lowering returns on their investments, they also penalise employees, by holding back wage increases or even employment levels, as shown by an abundant literature that is too often ignored in France.[16]

And though there may be cases where employees and shareholders are only lightly penalised, it is because tax incidence is borne by consumers, with a deterioration in the quality/price ratio. The digital tax is a perfect illustration of this failing. Though it is Intended to target the dominant Big Tech firms, their significant market power means that this tax ends up being paid by French households that consume digital services.

MISINTERPRETING FRANCE’S “GAFA TAX”

Officially, this tax was intended to correct an injustice.[17] Taxation of major digital firms (in particular Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, hence GAFA) was presented as abnormally low. The tax was supposed to correct this anomaly.

But taking tax incidence into account reveals a reality that runs counter to this narrative, with a tax that, while painless for the American players, is paid by their weaker European counterparts.

Sad to say, the French impact study was limited to general and even contradictory statements. It suggested that the Big Tech firms could seek to avoid passing the French tax onto their customers while acknowledging that they were in a position to do so because of the head start they enjoy.[18] It did not come up with any tax incidence numbers regarding companies that turn to these Big Tech firms and their consumers.

But it was clear that, in line with tax incidence theory, the U.S. Big Tech firms were able to shift most of the tax’s cost onto the French ecosystem. Benefiting from a head start and a critical mass, they could maintain their margins by eroding value sharing to the detriment of their partners or customers.

Back in March 2019, Deloitte & Taj warned of the impact of the future French law. According to its tax incidence numbers, 55% of the tax burden would be borne by consumers, 40% by businesses using digital platforms and only 5% by the big digital firms directly targeted by the law.[19]

Meanwhile, the Institut économique Molinari noted that a player like Amazon would have reason to pass on the extra cost from the tax to France. Given its global margin averaging 2.6% of revenues over the last 10 years, the creation of a 3% tax on some of its activities was far from insignificant. Amazon’s head start in e-commerce would put it in a position to shift the French tax onto its partners, adapting value-sharing rules and leading to lower earnings for businesses that use its marketplace to sell in France[20] This is exactly what happened.

A TAX ON CONSUMERS AND FRENCH DIGITAL PLAYERS

On October 1, 2019, Amazon confirmed the impact of the French tax on merchants using its platform. Commissions rose by a few tenths of a point to nearly 1.5 points, depending on the product, to offset the extra 3% cost resulting from the digital tax. In its news release, Amazon stated: “Because we operate in the highly competitive, low-margin retail sector and invest heavily in creating tools and services for our customers and vendor partners, we are not in a position to absorb an additional tax based on revenue and not on profit. As this tax is directly aimed at the marketplace services that are available to the companies we work with, we have no choice but to pass it along to them.”[21] As noted by a French journalist familiar with this issue, “We can therefore expect the vendors concerned, unless they sacrifice their margins, to pass along all or part of the rise in commissions through an increase in their prices. The GAFA tax would then end up being paid by customers.”[22]

Similarly, Apple indicated on September 1, 2020, that iOS developers will bear the burden of the GAFA tax. Developers’ earnings were “adjusted”, in other words reduced, to take account of the 3% levy applied by France on top of the VAT. The California-based firm left it up to the developers in question to raise the price of their apps, if they wished, and to shift the tax onto their consumers.”[23]

Moreover, the French tax does not weigh heavily from an economic standpoint on the major U.S. players initially targeted but does weigh harder on their business partners and customers, a point that the French administration acknowledges, though without questioning its approach.[24]

Another adverse effect is that this tax penalises mid-sized European digital firms above all. Since the likes of Amadeus, Critéo and Schibsted are not as powerful as the U.S. Big Tech firms, it is harder for them to shift the tax’s impact onto their present or future suppliers, partners or consumers. The tax’s economic effect on digital services will be borne by their teams and/or their shareholders. This is likely to result in lower compensation increases for employees, partners and shareholders and in higher risk for everyone due to the greater fragility of business models. This probably explains why the French digital ecosystem was particularly concerned by the institution of this new tax on digital services.

It is clear that dealing with a tax matter without analysing its incidence can lead only to mistaken conclusions.

In this respect, we can only recommend that lawmakers pay more attention to the basic notion of incidence, demanding real impact studies beforehand and establishing the criteria on which the laws are likely to be evaluated subsequently or, as the case may be, abandoned if it turns out they fail to produce the effects hoped for when they were voted on.

This approach is fundamental in analysing the impact of decisions in tax and regulatory matters. Various obligations intended to affect only corporations actually have an impact on consumers in the form of additional costs or greater complexity.

20210209Le_Point_Sur_incidence_fiscale_ENG

Notes

- KOTILIKOFF Laurence and SUMMERS Lawrence H. (1986), NBER Working Paper Series, Tax Incidence 3, Working Paper No. 1864, page 1.

- SMITH Adam (1776), The Wealth of Nations, Book 5, Chapter 2.

- SMITH Adam (1776), op. cit., Book 4, Chapter 6.

- RICARDO David (1817), On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Chapter IX.

- SAY Jean-Baptiste (1840), Cours complet d’économie politique pratique, Société Belge de librairie, for example page 497.

- SAY Jean-Baptiste (1840), op. cit., page 507. Full excerpt (translation): “The tax that the producer is obliged to pay is part of his production costs; it is a difficulty that he encounters along his way, which he can overcome only by paying a certain amount. And since he can continue to produce only as long as long as all his production costs (including his grief) are covered, he must raise the price of his products and in this way pass at least a part of the tax onto his consumers.”

- When elasticity is nil, demand does not move up or down when the price varies. Demand remains unchanged, regardless of the price. This applies in particular to basic necessities: although the price may rise, consumption is maintained, because there are few substitute products. When elasticity is negative, an upward price change is likely to cause a downward change in volumes of demand (and vice versa).

- SAUVEPLANE Paul and SIMULA Laurent for the Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires (2017), Où va l’impôt sur les sociétés ?, Special Report No. 6, Working document, page 5.

- SIMULA Laurent and TRANNOY Alain (2009), “Incidence de l’impôt sur les sociétés”, Revue française d’économie 2009/3 (Volume XXIV), pages 3 to 39.

- See for example LAURE Maurice (1956), Traité de politique fiscale, page 59.

- SIMULA Laurent and TRANNOY Alain (2009), op. cit., page 18.

- SIMULA Laurent and TRANNOY Alain (2009), op. cit., pages 3-4.

- See for example HARBERGER Arnold (1962), “The Incidence of the Corporate Income Tax”, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 70, No. 3, pages. 215-240.

- LEROY-BEAULIEU Paul (1910), Traité d’économie politique, page 877.

- LAURE Maurice (1956), op. cit., page 60.

- See for example SIMULA Laurent and TRANNOY Alain (2009), op. cit., pages 36-37, for a review of the literature, with Arulampalan et al. (2008) in particular estimating that that an additional $1 in income tax reduces wages by 92 cents in the long term; Felix (2006) estimating that a 10% rise in the corporate income tax reduces gross annual salary by 7%; Hasset and Mathur (2006) concluding that a 1% rise in the corporate income tax is associated with a 1% drop in the wage rate; Aus dem Moore and Kasten (2009) showing that a rise in the corporate income tax of $1 per employee results in a wage decrease of between 80 and 117 cents; Desai et al. (2007) finding that 45% to 75% of the corporate income tax is paid by labour, with the rest borne by capital.

- Taxation of the U.S. Internet giants was far from being as anecdotal as has been said. Analysis of their results shows that Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple paid or provisioned for 24% of their worldwide profits in corporate income tax during the five years preceding the adoption of the GAFA tax. This rate, slightly higher than the average observed in the OECD, is consistent with what was seen for large European companies. Over the last five years, the GAFA have borne one point more in taxation than the companies forming the Euro Stoxx 50 and Stoxx Europe 50 indices. See MARQUES Nicolas (2019), La taxation française des services numériques, un constat erroné, des effets pervers, March 2019, 58 pages.

- Excerpts from the impact study on the National Assembly bill creating a digital services tax and altering the course of the reduction in corporate income tax (translation): “Assuming that the players concerned may have some ability to avoid passing all of it along in their prices, it seems unlikely to have a significant macroeconomic impact. (…) Given the oligopolistic structure of the markets for the taxed services, most of the foreseeable return is concentrated in a small number of groups that capture most of the value created worldwide. The companies being taxed are likely to pass along part of the tax in the prices of services to other companies. This repercussion may be limited in particular by the desire of those subject to the tax to avoid eroding their competitiveness in relation to their rivals.” ECOE1902865L/Bleue-1 pages 19-20.

- PELLEFIGUE Julien (2019), Taxe sur les services numériques Etude d’impact économique, Deloitte Taj, March 2019, page 3.

- MARQUES Nicolas (2019), La taxation française des services numériques, un constat erroné, des effets pervers, Institut économique Molinari, Paris-Brussels, March 2019, page 31.

- Quoted by NOISETTE Thierry (2019), “Amazon ne veut pas de la taxe Gafa, vous allez donc payer plus cher”, Le Nouvel observateur, October 1, 2019.

- NOISETTE Thierry (2019), op. cit.

- “Your proceeds will … be adjusted in Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom and will be calculated based on the tax-exclusive price. However, prices on the App Store will not change.” Upcoming tax and price changes for apps and in-app purchases, accessible here.

- See for example National Assembly, response to Question No. 22418 from Philippe LATOMBE (Mouvement Démocrate et apparentés – Vendée). “The Amazon marketplace fully enters the field of the digital services tax. (…) It is not up to the government to comment on the choice announced by the group in question to raise its prices nor on its decision to present this choice as resulting from the application of a tax to which it is subject.”