The current pension reform ignores €61 billion in public revenues

Paris, December 10, 2019: The Institut économique Molinari has just published an original analysis of French pension reform as it affects retirement and public finances. Conclusions of this work, in partnership with Contrepoints, are the following:

- Pensions in France are not cheap. Based 98% on a pay-as-you-go system, they cost more than what is paid by our neighbours, who have accumulated capital to finance a portion of pension outlays.

- France’s shortfall amounts to about 2.6% of GDP per year in comparison to the OECD average. This is about €61 billion per year, or 19% of the pensions distributed. This amount to €3,750 per retiree each year

- The difference with the most forward-looking countries (Denmark or the Netherlands) amounts to €136 billion per year, equal to 42% of the pensions distributed or €8,400 per retiree.

- This shortfall leads to taxation that makes France less attractive. It explains the country’s inability to reduce unemployment and return to public surpluses at times of recovery, in contrast to what we see among our neighbours.

THE REFORM IS BASED ON INCOMPLETE DIAGOSTIC

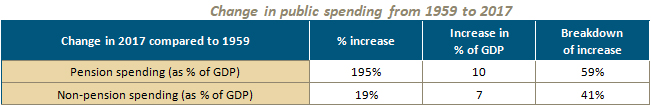

Pensions are absorbing a growing share of public spending (26%, compared to 13% in 1959). They account for 48% of spending by social security administrations and also for 12% of spending by the central government and 3% of spending by local administrations.

Pensions alone account for 59% of the rise in spending and public deficits from 1959 to 2017.

In the last 60 years, pension outlays have tripled in France with aging of the population. In 1959, there were 0.24 retirees per workforce member, and society spent 5.1% of GDP on pensions. By 2017, the proportion of retirees per worker had crept up to 0.74, and society was devoting 14.9% of GDP to pensions.

Meanwhile, unemployment and government deficits became structural. Unemployment rose almost six fold (from 1.5% to 8.6% in the third quarter of 2019, according to national statistics agency INSEE). The public accounts ceased to be in surplus and will run a deficit of 3.1% of GDP in 2019. The idea of a return to full employment and a rebalancing of public accounts has been abandoned by successive governments.

This economic analysis was not conducted in the run-up to the drafting of the campaign program. The program itself was inspired by projections from the Conseil d’orientation des retraites, amended due to an excess of optimism. Like other programs, it was developed without prior analysis of the indirect effects of aging on the public accounts, a sorry omission in a country that has not balanced its books since 1974.

Due to this impasse, the cleaning up of public finances is limited to little more than media hype.

A REFORM THAT FAILS TO DEAL WITH FRANCE’S UNDERLYING ISSUE

The benchmark produced by the IEM based on OECD data shows that pension funding costs more in France than elsewhere due to underdevelopment of the reserves of public pension plans and pension funds.

Each year, this underdevelopment costs France about 2.6% of GDP, or the equivalent of our public deficits.

Underdevelopment of the reserves of public pension systems (such as the Pensions Reserve Fund) accounts for 0.7 of the missing GDP points.

The shortage of private retirement savings (pension funds) accounts for 1.8 of the missing GDP points.

The discrepancy with the three European Union champions of retirement savings is even greater. If we had been as forward-looking as Denmark, the Netherlands or Sweden, our public and private pension funds would be generating 5.8 points of GDP per year. Compared to this leading trio, with their strong social tradition, the consecutive shortfalls resulting from the underdevelopment of retirement savings deprives us of €136 billion per year, amounting to 42% of the amounts allocated to pensions, or €8,400 per retiree.

Without income in the form of capital gains or dividends, pension financing is dependent on charges and taxes, along with deficits. This penalises economic growth, employment and net wage increases.

A REFORM THAT DESTABILISES BASIC PUBLIC AND PRIVATE PENSION INSTITUTIONS

In France, supplementary pension schemes are 49 times less developed than compulsory pension schemes.

Rather than encourage the creation of pension reserves or provisions, the reform reinforces the short-sighted flaws in our pension system. It spells the end for existing public institutions (Pensions Reserve Fund, Établissement de retraite additionnelle de la fonction publique) and private institutions (AGIRC-ARRCO, liberal profession retirement funds) that have shown foresight and responsibility, operating free of deficits and creating savings that enhance the return on investment of pension contributions.

The reform, based on accounting logic, fails to take account of France’s institutional wealth or of the scope of relevant incentive structures serving as long-term commitments. It backtracks on the compromises instituted at Liberation, maintaining a plurality of players who follow forms of professional logic. It proposes creation of a single pension fund guided by the government, which has not always excelled at managing its pension commitments. It could prove costly, much like the flaws noted by the Court of Auditors during previous reforms of special systems. It lacks constitutional-type rule that would help preserve balances and reserves (golden rule).

It is true that part of the May 2019 PACTE law (Action Plan for Business Growth and Transformation) is intended to encourage the establishment of supplementary retirement savings. Although this is a step in the right direction, precedents in France (the Fillon law of 2003) and elsewhere (Germany’s Riester pensions) show that these voluntary approaches are slow to produce results.

A REFORM THAT IS LIMITED TO A ZERO-SUM GAME

While the 2003 reform had adeptly created new rights on an economic and responsible basis with the establishment of a defined-benefit public pension fund (the Établissement de retraite additionnelle de la fonction publique), the government’s new reform seeks to create a new universal pay-as-you-go fund.

As might be expected, this reinforces fear and opposition, with the adjustments being limited to social contributions (their increase penalises the purchasing power of assets and employment), to retirement benefits (their lower revaluation penalises the purchasing power of the retired) and to working time. By missing out on what is needed in France, it risks creating maximum opposition with minimal gain. Nearly all civil service pensions, and those of private-sector employees, would continue to be funded by compulsory levies or public debt. Retirement savings would remain solely the prerogative of the far-sighted, leaving much of the French population on the sidelines.

QUOTES

Nicolas Marques, General Manager of the Institut économique Molinari, co-author of the study

“Under the guise of simplification, fairness and efficiency, which remain to be proven, the French government is in the process of organising a nationalisation of old-age insurance funds and independent pension plans. This approach, presented as a modern, pragmatic choice, is far from innocuous. It is similar to the nationalisation of the insurance and banking sectors after the Second World War, or establishment of the 35-hour workweek in the early 2000s. It will not in any way improve financial balances, and it will not alleviate the cost of funding pensions. Worse yet, it will reinforce a fundamental French flaw, with the under-sizing of retirement savings.

“Contrary to what the reform proposes, there is a need to ramp up public or private pension funds, as proposed 110 years ago by Jean Jaurès. Only by adding a significant dose of retirement savings and by ramping up public or private pension funds can we change the outcome. Enabling pensions to be partly funded by dividends and capital gains would reduce the dependency on charges and taxes that penalises growth, employment and wages.”

Cécile Philippe, President of the Institut économique Molinari, co-author of the study

“Our pension system does not need universality or homogenisation but rather should provide pensions with a decent quality/price ratio.

“The current reform runs counter to common sense, implementing a vast shift to state control, a paradoxical step given that the state has been incapable of generating surpluses since 1974 in France.

“It would occur to the detriment of virtuous public or private institutions that, without running deficits, have acted responsibly in creating retirement savings: the Pensions Reserve Fund, the Etablissement de retraite additionnelle de la fonction publique, AGIRC-ARRCO, the liberal profession retirement funds and so on. We should turn to this diversity and move away from the zero-sum game in which we have been stuck rather than fighting it.”

ABOUT THE INSTITUT ECONOMIQUE MOLINARI AND CONTREPOINTS

The Institut économique Molinari (Paris-Brussels) is an independent research and education organisation. It seeks to stimulate the economic approach in public policy analysis, offering innovative alternative solutions conducive to the prosperity of all individuals making up society.

Contrepoints is the leading liberal daily news website in French. Contrepoints promotes a free society by covering politics, culture and ideas for a monthly audience of 2 million readers, viewers and listeners.

THE STUDY IS AVAILABLE (IN FRENCH) HERE.

FOR INFORMATION OR INTERVIEWS, CONTACT:

Cécile Philippe, President, Institut économique Molinari

(Paris, Brussels, in French or English)

cecile@institutmolinari.org

+33 6 78 86 98 58

Nicolas Marques, Managing Director, Institut économique Molinari

(Paris, in French)

nicolas@institutmolinari.org

+ 33 6 64 94 80 61