Economy Will Be Critical Front in French President Hollande’s War Against Terror

Article by Simon Nixon published on November 22, 2015, in The Wall Street Journal.

President François Hollande has declared that France is at war. It is a war that will be fought on many fronts. He has already stepped up bombing raids on Islamic State strongholds in Syria, declared a state of emergency at home, and promised a substantial increase in spending on defense and security.

But while these steps may be essential to address the immediate terrorist threat, Mr. Hollande’s war will also need to be waged on the economic front to succeed in the long term. France’s broader battle is to head off the homegrown threat by opening up more promising opportunities for those most at risk of being radicalized. That, in part, requires a vibrant economy able to create worthwhile jobs.

Unemployment is the Achilles’ heel of Mr. Hollande’s presidency. When he took office, the jobless rate stood at 9.8% and he vowed not to stand for re-election in 2017 unless he had succeeded in reversing its rising trend. But the European Commission forecasts that the unemployment rate will end this year at 10.4% and remain flat next year, falling only to 10.2% by the end of 2017. Meanwhile, youth unemployment of 24% is above the European Union average, and the unskilled unemployment rate is three times the skilled rate. The level of French joblessness at which inflation is likely to start rising again may now be 9.5%, according to the International Monetary Fund. That points to a terrible waste of human potential.

There is no mystery as to why the French economy is performing so poorly. There is broad agreement among economists that French public spending at 57.5% of gross domestic product in 2014—some 12% above the EU average—and tax receipts at 49% of GDP are much too high. At the same time, France’s labor market is much too rigid—France currently ranks 103 out of 144 countries for labor-market flexibility, according to the World Economic Forum—and years of minimum wage increases well ahead of productivity growth have undermined competitiveness. As a result, corporate margins and productivity growth have deteriorated, leading to sharp falls in corporate investment, which in turn bodes ill for longer-term productivity growth and job creation.

To address these weakness, the French government has cut corporate taxes by €30 billion and has secured an agreement with trade unions for some relaxation of labor rules. But few economists think this goes far enough. The European Commission and the IMF have both noted that the labor market will remain very rigid, with wage bargaining still taking place at national rather than company level. Nor is there much prospect of the tax burden coming down in even the medium term: To put public debt—now approaching 100% of GDP—on a declining trajectory and create fiscal space for tax cuts beyond 2020, Paris would need to freeze public spending in real terms, the IMF advised earlier this year. Instead, government spending is set to rise by 1.6% this year and 1.2% next.

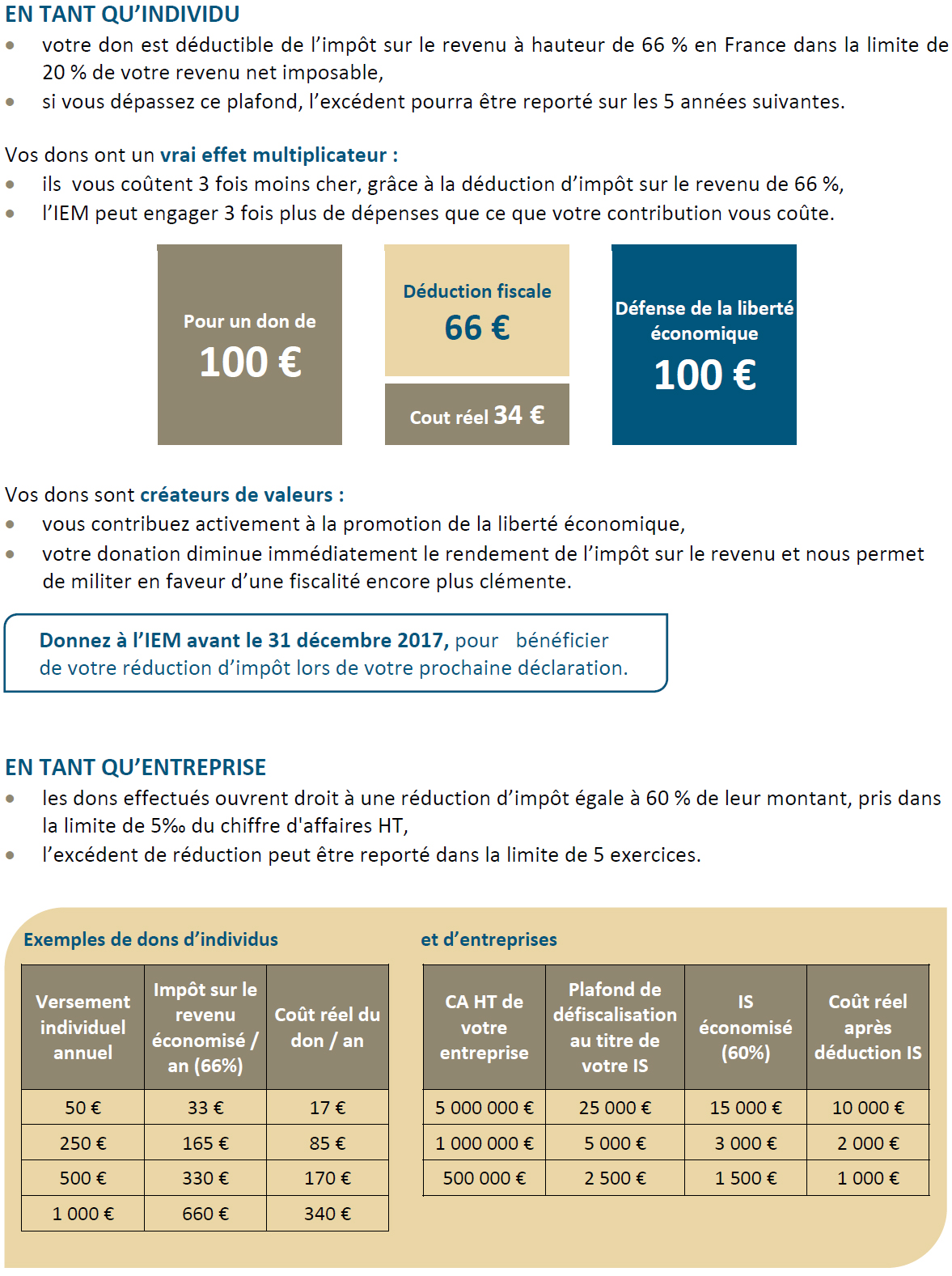

The latest terrorist attacks could be a catalyst for rethinking an outdated economic model that protects insiders at the expense of outsiders and whose high levels of public spending have manifestly failed to deliver social cohesion where it matters. Until recently, France’s reformers, including the country’s small network of free-market think tanks such as Generation Libre and the Institute Economique Molinari, felt the tide was flowing their way. L’Expansion, a popular weekly magazine, confirmed the growing influence of free-market ideas with a recent cover story on “Les Nouveaux Liberaux” featuring flattering profiles of prominent campaigners.

But the risk is that the attacks will produce the opposite reaction. The Paris attacks may fuel support for the National Front whose leader Marine Le Pen has based her pitch to voters on a combination of nationalist opposition to the EU with strong support for high degrees of social and economic protection. French ministers say Mr. Hollande, having swung away in the past two years from the left-wing positions that got him elected, is likely to swing back ahead of the 2017 presidential election: the government’s agenda next year is likely to focus on left-wing priorities such as introducing new employment protections for freelance workers.

Meanwhile, Mr. Hollande has made clear that France is unlikely to meet its eurozone deficit targets as a result of higher defense and security spending. That may give the French economy a short-term boost, but risks a further deterioration in productivity and delays the possibility of tax cuts. It may also further undermine confidence in the eurozone’s fiscal rules. Under the circumstances, no one is likely to object to France’s extra spending and the European Commission has already signaled its willingness to be flexible. But the reality is that there were doubts about France’s willingness to meet its targets—and the commission’s willingness to enforce the rules—before the attacks. That could complicate efforts to develop new risk-sharing mechanisms that many economists believe are essential to boost confidence in the wider eurozone.

As with Mr. Hollande’s war against Islamic State, the outcome of his economic battle will reverberate well beyond France.