On November 12, the French government ran out of revenues and ended the year going further into debt – The government in France is among the EU’s three deficit leaders

Paris, November 11, 2019: The Institut économique Molinari has just calculated the dates when European Union (EU) governments spent all of their annual revenues for 2018.

THE FIFTH EDITION OF THIS STUDY SHOWS THAT:

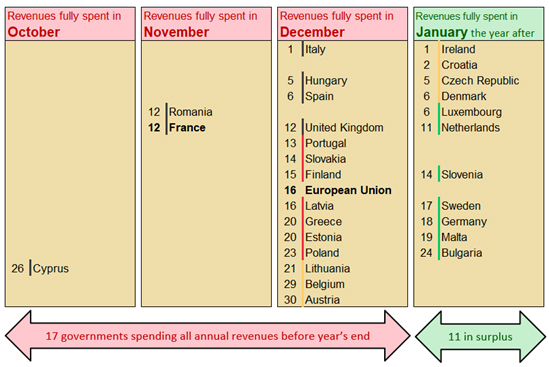

- Central administrations in EU countries had, on average, exhausted their revenues on December 16, or 16 days before year-end. This is four days later than in 2017, a notable improvement.

- Among the EU’s 28 central administrations, 11 were in surplus in 2018, 14 exhausted their revenues in December and three had spent the full amounts earlier.

- France’s central administration had spent all its revenues on November 12, or 49 days before the close of the budget cycle.

- The discrepancy between France and the EU average is 33 days. It grew by four days between 2018 and 2017, despite favourable economic conditions.

- Projections by the IEM show that the French situation is not becoming normalised: unfunded expenditures by France’s central administration are likely to rise again – to 62 days in 2019 and 59 days in 2020.

Calendar of dates when EU central administrations have spent all their revenues

OTHER LESSONS

Central administrations are the main source of public deficits in the EU

Despite favourable economic conditions, central governments remain the dark spot in European public finances. In the EU as a whole, central administrations account for the bulk of the gaps in public accounts, with 16 unfunded days.

The administrations of federated states have been in balance since 2017 and generated a four-day surplus in 2018. Local administrations have been in balance since 2014 and produced a two-day surplus last year. Social security administrations have been in balance since 2016 and garnered a six-day surplus last year. Public administrations over all produced a six-day deficit.

Three-month discrepancy between the central administrations with the highest surplus or deficit

The champions in 2018 were Bulgaria, with a surplus equal to 23 days’ spending, Malta (18 days), Germany (17 days) and Sweden (17 days). Their revenues for the year enabled them to fund all their expenditures and to pay down debt.

Sweden has been in the quartet with the greatest surpluses for the last four years, Malta for three years and Bulgaria for two years.

At the rear of the pack are France and Romania (with a deficit equal to 49 days’ spending) and Cyprus (deficit equal to 66 days’).

France and Romania have become familiar with weak performances. France has been in the trio of states with the greatest imbalances for the last three years and Romania for the last two years.

The position of France’s central administration is precarious

While central administrations in the EU have used the last nine years to reduce their deficits, this has not been the case with France. The post-crisis (2009-2013) account rebalancing movement ran out of steam sooner than elsewhere, going back six years.

In the last five years, France’s central administration has reduced its deficit by only two days. Meanwhile, EU countries as a whole reduced their deficits by 25 days.

Since the deepest days of the crisis, public spending has declined four times more slowly in France than the EU average. It barely ebbed between 2009 and 2018 (-1.2%) while falling significantly in the EU (-4.4%). France put a premature halt to the traditional post-crisis weight reduction phase in public spending. Accordingly, adjustment occurred on the revenue side, with revenues in France rising at more than double the EU pace (+3.5% compared to +1.5%).

In France, three-quarters of the post-crisis adjustment came from the usual tax increases, while spending cuts accounted for just one-quarter. In the EU as a whole, the choice was the diametrical opposite, with adjustment relying three-quarters on spending cuts and one-quarter on tax hikes.

At this stage, France has not done as well as the rest of the EU in recovering financial leeway. The crisis is leaving triple the impact on the public finances. Public revenues and expenditures are up by more than three points of GDP, compared to an EU average of one point. The public deficit remains three times as high in France (2.5% of GDP) as the EU average (0.7% of GDP).

This inability to achieve lasting improvement in the public accounts during an upturn has not vanished, despite favourable economic conditions. Worse yet, each phase of “consolidation” seems more precarious than the one before. Between 1999 and 2001, French deficits averaged more than 30 days of spending per year. Between 2004 and 2007, they averaged 40 days and, between 2013 and 2017, 50 days.

RESOURCES

The study titled “The day when European Union countries ran out of revenues – 5th Edition” is available (in French only) on our website.

European charts and graphs (Datawrapper) are available.

QUOTES

Cécile Philippe, President of the Institut économique Molinari (IEM) and co-author

“In France, the central administration lives on credit for 49 days a year. It runs out of revenues on November 12, more than a month before the other European Union governments, which on average are in balance until December 16.

“Putting the central administration’s accounts in order should be the top priority. Local bodies and social security administrations in France are in balance. Moreover, the unhappy experience of our southern neighbours shows that an inability to reduce public deficits during an upturn creates exposure to social costs and painful adjustments in a time of decline.”

Nicolas Marques, General Manager of the Institut économique Molinari (IEM) and co-author

“The position of the French central administration is a cause of great concern. Since 1980, every budget has been out of balance, and the date when all revenues have been consumed has moved forward by 1.2 days per year.

“The government is no longer managing to use periods of respite to rebalance its budget. It is running out of revenues two months before the end of the year, while our neighbours’ deficits amount to only two weeks of unfunded expenditures.

“At this stage, nothing is holding back this drift. We are headed toward 62 days of unfunded public expenditures in 2019 and 59 days in 2020.”

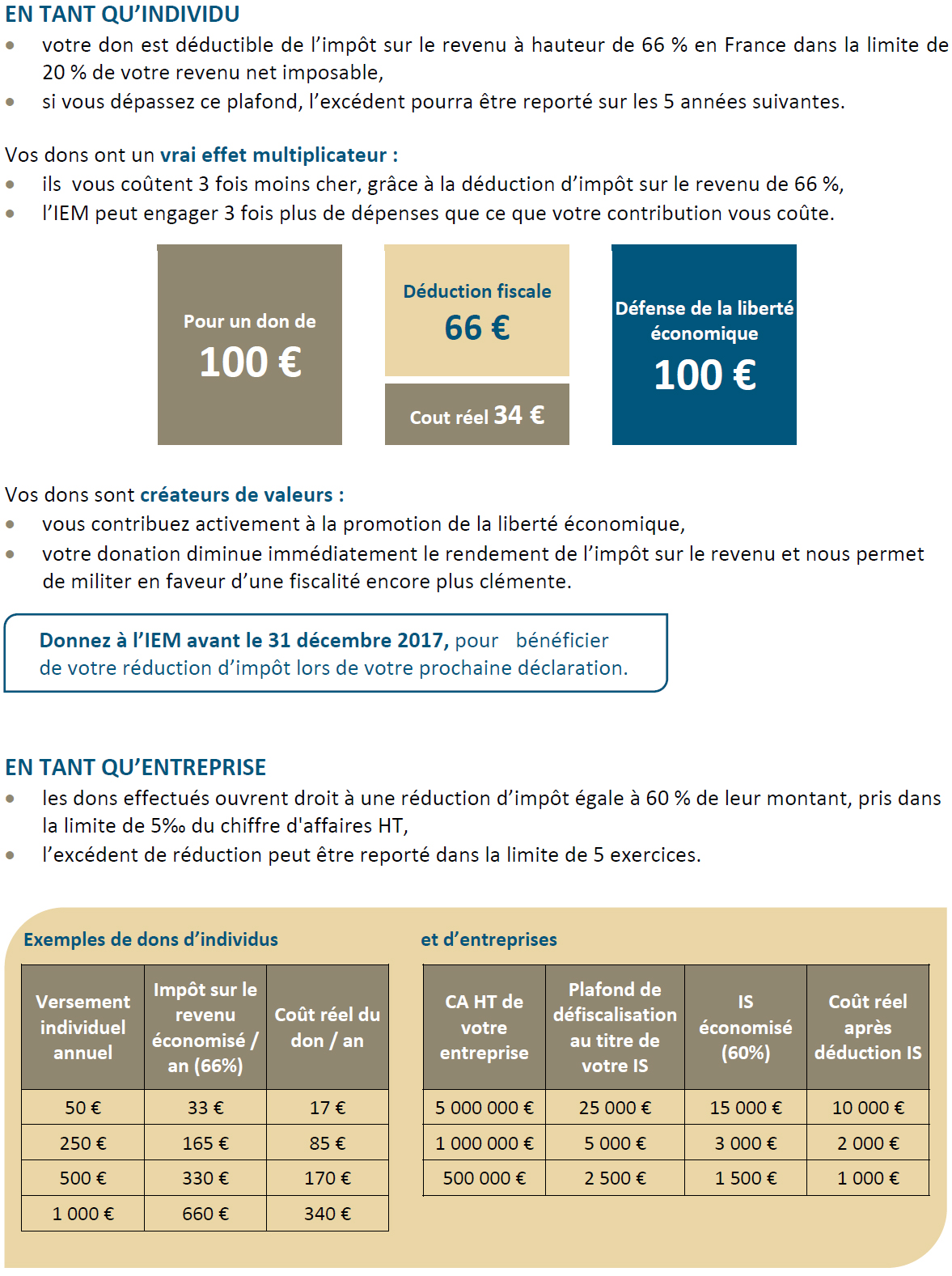

ABOUT THE IEM

The Institut économique Molinari (IEM) is a research and education organisation with the mission of promoting individual freedom and responsibility. The Institute aims to facilitate change by spurring debate around preconceived ideas that engender the status quo. It seeks to stimulate the emergence of new consensus positions by offering an economic analysis of public policy, demonstrating the value of dialogue and indicating the benefits of more lenient regulation and taxation. The IEM is a non-profit organisation financed by voluntary contributions from its members: individuals, foundations and businesses. Putting intellectual independence foremost, it accepts no public subsidies.