Taxation and its negative impact on business investment activities

Economic Note

Economic Note prepared by Gabriel A. Giménez Roche, associate researcher at the Institut économique Molinari.

Read the Economic Note in PDF format

Read the Media release : Corporate taxation slows down economic recovery in France – Tax hamonisation with our neighbours would require a 20% cut in the corporate tax burden

France’s fiscal recovery following the 2008 crisis has been slowing down ever since 2012. Although it is evident that this slump in tax revenue is due to slower activity, this can no longer be explained by the crisis context. Indeed, most foreign trade partners have recovered more strongly than France, and French exports are now at higher levels than before the crisis.(1) Worse still, the first half of 2015 saw a 48% drop in corporate income tax revenue.(2) It is true that this is partly due to tax rebates under the CICE, a programme meant to encourage competitiveness and employment. But the decline is much sharper than the anticipated rebates. This suggests that the broadening of the tax base expected under the rebate programme is not really occurring and that corporate taxation remains a problem.

WHAT IS CORPORATE TAXATION AND WHY IT IS IMPORTANT?

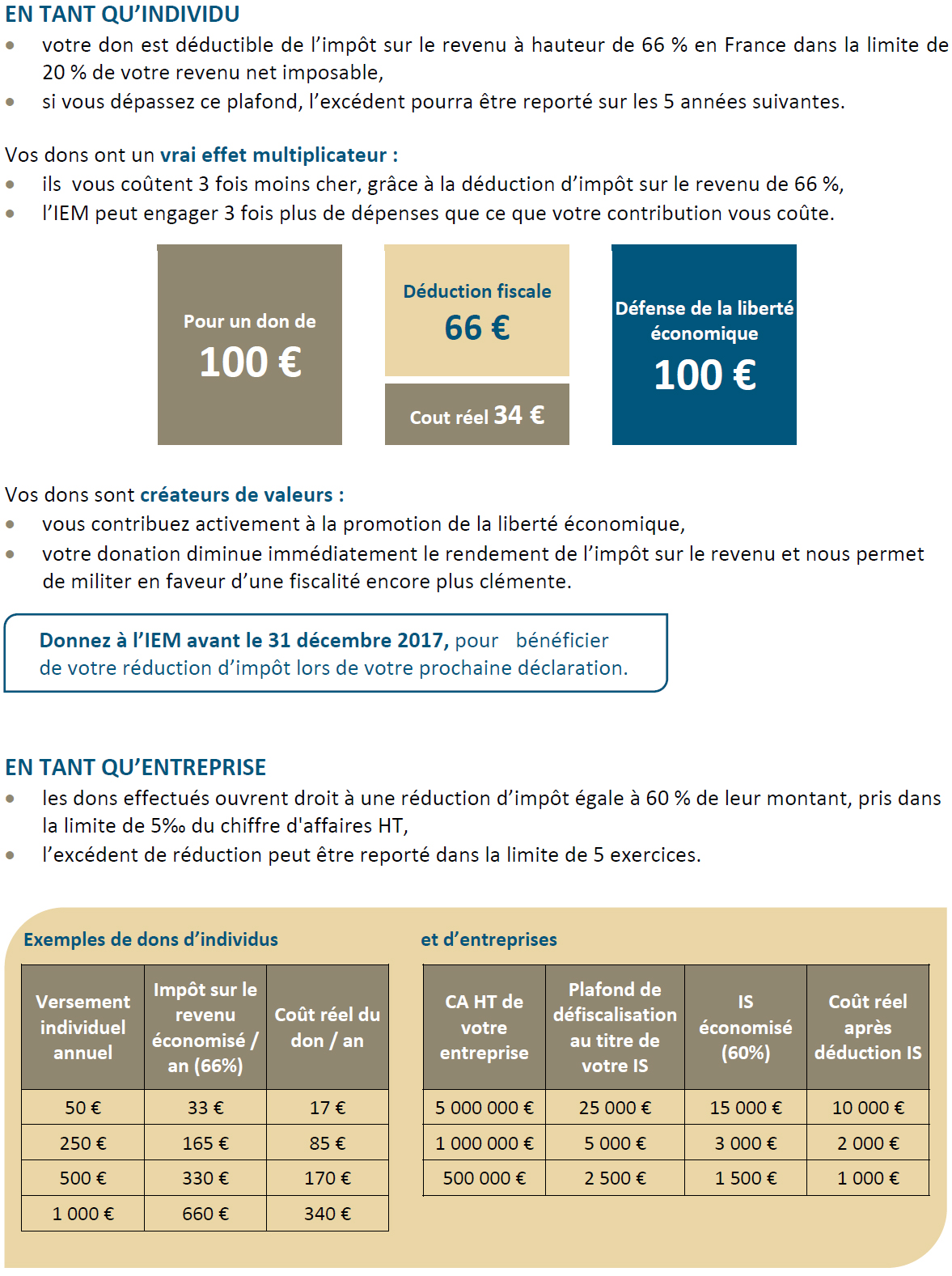

Where corporate taxation is concerned, what often comes to mind is the 33.3% corporate income tax rate. However, this is not the only tax that entrepreneurs consider when deciding whether to create a company, expand an existing firm or invest in a particular country. At present, the corporate tax burden imposed on a small or medium business in France can amount to over 60% of its pre- tax net profit(3) (see Figure 1). Indeed, corporate taxation comprises all taxes paid by a business. In addition to the corporate income tax paid on earnings, it also includes employer-borne social security contributions paid on payroll, real estate taxes and many other minor taxes. Each one of these taxes may have different treatments, interpretations, and allowances that add up to greater tax complexity.

Corporate taxation also includes taxes indirectly borne by businesses since they affect shareholders and creditors who provide financing. These include taxes on dividends, capital gains and business-related interest. Moreover, some companies face surtaxes depending on their area of activity or product type, or simply because they exceed a certain turnover level.

Corporate taxation is of great concern in investors’ decisions and hence in economic growth and employment. Complex and excessive taxation deters foreign investors, drives out domestic investors, curbs entrepreneurship, and results in deadweight losses due to tax compliance and tax avoidance costs. Friendly taxation, meanwhile, broadens the tax base by attracting foreign investment, encouraging domestic investment and stimulating entrepreneurship, thus entailing greater tax compliance.

WHERE DOES FRANCE STAND?

Slower activity in France is most probably related to the corporate tax burden imposed on French businesses during tenuous times. In actual fact, firms and investors are adjusting to France’s revamped corporate tax burden after an initial tax shock from which they could not escape. The introduction of the CICE does not counter this shock because it involves only firms that are actively increasing their workforces, in other words growing. A company facing hard times can hardly think about hiring people but has to pay its employer-borne social security contributions at the full rate. Moreover, from 2011 to 2015, companies have faced an exceptional surtax of 10.7% on top of their corporate income tax.(4) This can effectively raise the tax rate from 33.3% to almost 37%. Investors who had their incomes tax capped at 39.5% under a specific regime before 2012(5) now see their capital gains taxed in full under the personal income tax system, with its 45% top marginal rate. With the wealth tax included, investors can potentially be taxed at up to 70% of their gains.

MAIN ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES

Economic growth

Taxation has different impacts depending on the form it assumes. Corporate and shareholder taxes reduce the capital funds available to make investments and build a greater and more productive structure. This means that growth in the volume of productivity-boosting equipment, facilities and knowledge resulting in enhanced purchasing power for investors and employees alike — that is, capital accumulation in the economy — decelerates.(6)

The fact is, firms are the source of most income circulating in any economy. Although it is true that their income depends on their clients’ wealth, firms are the entities that conduct the actual redistribution of income in the economy. Profits are a sign that a firm generated more wealth than is used in production. This entails a potential increase in income for various agents. Shareholders obtain dividends, and employees may see pay rises in the form of profit-sharing. Any profit that is retained as corporate savings implies future investment that generates new income flows to current and future employees. Taxing corporate income is therefore equivalent to reducing all these income flows.

Recent studies point out how harmful the corporate income tax can be to economic growth. In a thorough study analysing the impact of some 104 tax changes in the post-WWII United States, Christina and David Romer show that a 1% federal tax increase results in a 3% fall in output after two years.(7) In a broader study covering 15 developed countries, the IMF examines 170 fiscal consolidations over more than 30 years, with a similar result: a 1% tax increase reduces GDP by 1.3% after two years.(8) Other studies based on 20 OECD countries conclude that corporate income tax is the form of taxation most harmful to investment and productivity growth.(9) Indeed, a common finding is that reducing corporate income tax by 1% could result in GDP gains of 0.1% to 0.6%.(10)

A number of studies show that a rearrangement of a country’s tax structure by shifting the tax burden from income taxes to consumption taxes could make taxation more efficient and friendlier to economic growth.(11) This may make sense if the consumption tax is low to begin with. But if it is already high, as it is in France, shifting the burden would be a problem. Producers facing low price sensitivity in demand could more easily shift the tax to consumers. But this leaves consumers with less income to spend on other products and reduces their ability to save. Therefore, other producers are indirectly hurt by taxes on these products, and the economy in general suffers from the reduced savings as investment decelerates. On the other hand, producers coping with price-sensitive demand may have to absorb the tax hike in order to avoid a drop in sales, cutting their margins rather than shift the tax. This amounts to taxing production instead of consumption, hurting reinvestment. In the end, shifting the tax burden to consumption ultimately impacts capital accumulation.

Impact on foreign direct investment

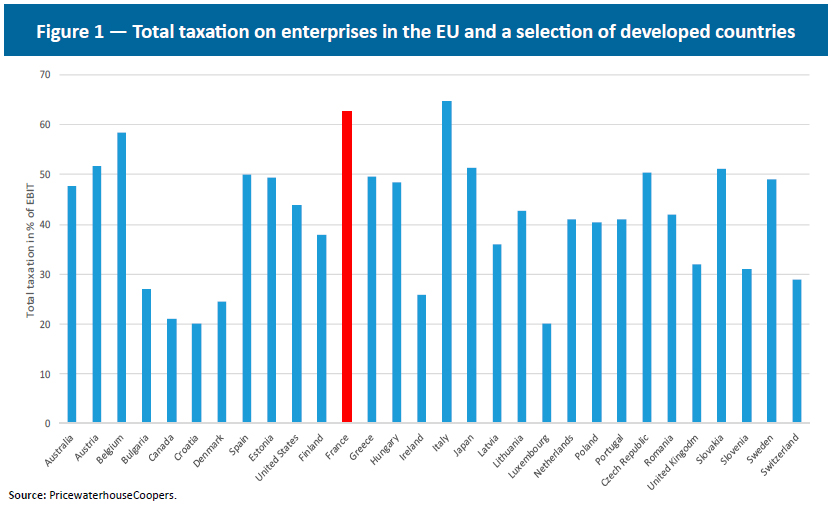

In addition to the distortions it causes to economic growth, corporate taxation influences foreign direct investment (FDI) decisions. It creates a wedge between pre- and post-tax returns on FDI. The greater the wedge, the lower the incentive to undertake FDI in a given country.(12) Of course, this does not mean that high taxation will necessarily prevent investment in a country. Other considerations such as market openness, labour costs and regulatory hurdles are also taken into account. However, these advantages can rapidly be corroded if the wedge on FDI returns is too great, favouring low-tax countries to the detriment of high-tax jurisdictions.(13) In France, foreign investment flows between 2010 and 2013 were 44.87% lower than in the 2000-2003 period. Flows are five times lower than in the previous decade.(14)

This can be seen in France’s performance in competitiveness indices. In the International Tax Competitiveness Index prepared by the Tax Foundation, France ranks last among OECD countries.(15) In the Global Competitiveness Index ranking published by the World Economic Forum, France does better but still ranks far below its main economic rivals in the European Union. France ranks 22nd in the 2015 edition, while Germany and the United Kingdom are part of both the Global and European Top 10.

Regardless of the credibility attached to these competitiveness rankings, it is undeniable that France is losing attractiveness in Europe. Its main economic rivals in the region of similar population and GDP size, namely, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, are all performing better than France in inward FDI flows. What is even more worrisome is that even Italy, historically an FDI underperformer compared to its neighbours, has now overtaken France (see Figure 2).

Impact on productivity: savings, tax compliance

The negative impacts of taxation on productivity involve many channels. Taxation of corporate income, for instance, punishes savings not only by the firm but also by its shareholders, who usually face double taxation. The same income — in the form of corporate profits — is first taxed under the weight of the corporate income tax and then, when distributed as dividends, it falls under the yoke of personal income tax. In France, double taxation can easily reach 60% of the gross realized gains from an investor’s holding in a company, the highest in the OECD.(16) Double taxation makes equity investment more expensive and leads corporations to choose debt finance over equity finance. In times of economic euphoria, corporations thus take on too much debt, which can prove fatal when a crisis sets in. Double taxation also penalises long-term investment when debt finance is not readily available to a company. Consequently, firms may choose to focus on short-term projects, with more emphasis on labour than on capital spending. While this may seem beneficial for labour, the contrary is true. With less investment in technology and capital goods, labour becomes less productive and therefore yields lower returns. Wages can thus be depressed by taxation of profits.

Another channel is the bureaucratic costs involved in tax compliance. The complexity and lack of transparency of taxation means that its costs can be quite significant. Companies hire experts to make sense of the law and avoid over- or underpayment. Administrative costs are pushed up by the documentation needed to justify a tax position. This is particularly harmful to businesses that must incur artificial costs completely unrelated to their production and commercial activities.(17) In a survey of the most recent academic studies on tax compliance costs, Fichtner and Feldman find that the hidden costs of tax compliance vary between 1.3% and 6.1% of GDP, producing a tax gap of 2.8% of GDP for the U.S. federal government.(18)

Tax avoidance

Tax avoidance refers to all practices and schemes adopted by companies to reduce their tax burden legally. In spite of the bad press it draws, tax avoidance is a competitive necessity in a globalized world, where markets are no longer limited to domestic consumers and investors. Tax avoidance satisfies the corporate performance requirements of shareholders and creditors with respect to gains from dividends and interest. This makes investors more receptive to management, which is then better able to undertake longer-term projects that build up capital, increase productivity and generate new production outlets. Labour remuneration and employment improve. This also means that shareholders will keep investing in the firm for a longer period, instead of selling their shares in a speculative move as soon as they make a capital gain. Moreover, tax avoidance makes a company more competitive. By increasing its available income, tax avoidance allows for investment on new organizational methods and technology that can improve its cost structure vis-à-vis its competitors. Furthermore, the availability of greater capital reserves helps a company deal with hard times more effectively.

Tax avoidance does not involve all companies. Nor is it limited to large companies. Only the more mobile companies, in terms of either production or sales, usually those with much of their income coming from foreign markets, can expect to enjoy tax avoidance advantages beyond domestic tax shelters. Big multinationals benefit from large incomes that enable them to implement complex tax avoidance schemes involving parent and subsidiary companies abroad. Very small companies can benefit from various domestic tax shelters and subsidies that are akin to tax avoidance. Only less mobile companies, unable to bear the vicissitudes of tax avoidance, must carry the full tax burden.(19) This foster inequality, with such companies unable to shift their incomes to domestic tax shelters or lower-tax countries.(20) Non-tax-avoiding firms thus lose competitiveness, jeopardising their ability to invest and employ.

In any case, tax avoidance helps undo tax policies that rely on higher tax rates to increase government revenue. The higher the rates, the greater the tax compliance costs are and the greater the incentives to engage in tax avoidance. Fighting tax avoidance through regulation may prove counterproductive to the government for five reasons.(21) First, whenever tax authorities try to regulate tax avoidance, they make current tax regulation longer and more complex. This increases tax compliance costs, which reinforces the incentive for tax avoidance or worse, fiscal exile. Second, the resulting higher costs of tax compliance also increase the authorities’ administrative tax surveillance and collection costs. Third, any reaction against tax avoidance is met by growth in the tax avoidance lobby industry, funnelling company funds that would otherwise be used in production. Fourth, the increase in tax regulation entails growth in the tax specialist industry within large corporations and accounting firms, further diverting funds from productive use. Finally, government risks losing revenue as tax avoidance rises or as tax-avoiding companies simply decide to leave their territory.

CONCLUSION

Corporate taxation, particularly in France, is a drag on the economy. High-taxing governments miss the point that wealth is generated within companies and that this wealth is continuously redistributed as remuneration to employees and to investors. However, companies need capital to generate wealth, and this comes from investors. Corporate taxation penalises investors and later penalises employees too as companies invest less or leave the country.

Companies are increasingly integrated into a global economy and are no longer limited to their original domestic markets. In order to stay on course, France should at least harmonise its tax burden and regulatory complexity to the same level as the rest of the world. This implies a decline of more than 20% in overall corporate taxation. This would merely make France as competitive as its better-performing neighbours of similar size, such as Germany and the United Kingdom. If France were to aim at becoming more competitive, then an effort of more than 20% would be necessary. This would not necessarily cause a decline in government revenues. On the contrary, if corporate taxation is drastically reduced, so are tax compliance costs, resulting in a broadening of the tax base. This has worked for France’s partners in the European Union. Nothing would prevent it from working for France as well.

NOTES

1. Prior to the 2008 crisis, French exports reached a peak of €138 billion. Today, France is reaching €160 billion in exports. Sources: European Central Bank and Eurostat.

2. Raphaël Legendre, “Impôt sur les sociétés : les recettes plongent de moitié.” L’Opinion (Retrieved 1 November 2015).

3. The typical company is a medium-sized (60 employees) limited liability company, realizing a pre-tax 20% gross margin. For the full profile on France and the description of the typical company see PricewaterhouseCoopers (2015), Paying Taxes 2015: The Global Picture, pp. 95-98, 121-132 (Retrieved 9 November 2015).

4. Taxable corporate income in France refers to net earnings before tax. From the end of 2011 to the end of 2013, the surtax was 5%. After that, it became 10.7% up to late 2015. Source: impots.gouv.fr.

5. Before the tax reform of 2012, capital and surplus-value gains were taxed according to the underlying investment concerned (mandatory social security contributions already included): real estate, 32%; equity securities, 32.5%; dividends, 36.5%, interest, 39.5%. Today all these gains are taxed under the personal income tax regime. See: “Cinq questions sur la nouvelle fiscalité du capital.” L’Express/L’Expansion (Retrieved 5 November 2015).

6. The reader should not confuse capital accumulation with capital concentration. Capital concentration is the amassing of the economy’s accumulated capital by a few individuals or institutions to the detriment of others.

7. Christina Romer and David Romer (2010), “The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: Estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks,” American Economic Review 100 (3), pp. 763-801.

8. IMF (2010), “Will it hurt? The macroeconomic effects of fiscal consolidation,” in World Economic Outlook: Recovery, Risk, and Rebalancing, pp. 93-124.

9. Norman Gemmel, Richard Kneller and Ismael Sanz (2011), “The timing and persistence of fiscal policy impacts on growth: Evidence from OECD countries,” Economic Journal 121 (550), pp. F33-F58. Jens Arnold, et al. (2011), “Tax policy for economic recovery and growth,” Economic Journal 121(550), pp. F59-F80.

10. In their study of Canadian provinces, Ferede and Dahlby find that reducing the corporate income tax by 1% raises annual growth by 0.1% to 0.2%. Ergete Ferede and Bev Dahlby (2012), “The impact of tax cuts on economic growth: Evidence from the Canadian provinces,” National Tax Journal 65 (3), pp. 563-594. Mertens and Ravn, after analyzing exogenous changes in corporate taxes in post-WWII America, show that a 1% cut in corporate income tax results in 0.6% GDP growth after a year. Karel Mertens and Morten O. Ravn (2012), “Empirical evidence on the aggregate effects of anticipated and unanticipated us tax policy shocks,” American Economic Review 4 (2), pp. 145-181. Barro and Redlick calculate using U.S. data from 1912 to 2006 that a 1% cut in the average marginal tax rate can result in a 0.5% positive impact on GDP per capita. Robert J. Barro and C. J. Redlick (2011), “Macroeconomic effects from government purchases and taxes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (1), pp. 51-102. Finally, Lee and Gordon find after a cross-sectional analysis of 70 countries from 1980-1997 that a 1% cut of the income tax raises annual growth by 0.1% to 0.2%. Young Lee and Roger Gordon (2005), “Tax structure and economic growth,” Journal of Public Economics 89 (5-6), pp. 1027-1043.

11. Jens Arnold, et al. (2011), “Tax policy for economic recovery and growth,” Economic Journal 121(550), pp. F59-F80. OECD (2009), Economic Policy Reforms: Going for Growth, pp. 143-161. Vartia, et al. (2008), “Taxation and economic growth,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers.

12. Laura Vartia, et al. (2006), “Taxation and business environment as drivers of foreign direct investment in OECD countries,” OECD Economic Studies (2), pp. 7-38.

13. OECD (2009), Economic Policy Reforms: Going for Growth, pp. 143-161.

14. The average for the 2000-2003 period was 185,360 million dollars against only 102,178 dollars for the 2010-2013 period. It is also worth remarking that between 2000 and 2010, the average flow of FDI in France was 559,241 million dollars. Source: OECD.

15. “2015 International Tax Competitiveness Index.” Tax Foundation (Retrieved 5 November 2015).

16. Michelle Harding (2013), “Taxation of dividend, interest, and capital gain income,” OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 19, OECD Publishing.

17. A good example in France that goes beyond fiscal compliance costs can be found here: “Bureaucratie à la française: le témoignage choc d’un patron de PME.” Challenges (Retrieved 31 October 2015).

18. Jason J. Fichter and Jacob M. Feldman (2013), “The hidden costs of tax compliance,” Mercatus Center — George Mason University.

19. In France, the big losers are actually small and medium companies (between 10 and 250 employees) that pay more than 30% of net earnings as corporate income tax, while the corporate income tax of large (+250 employees) and very small companies (< 10 employees) range only from 12% to 23% of net earnings (Source: Base de données ESANE de l’INSEE). Indeed, French SMEs seem to be too small and domestically-based to benefit from foreign-based tax avoidance schemes while also being too big to benefit fully from domestic-based tax shelters and production incentives.

20. Grahame Dowling (2014), “The curious case of corporate tax avoidance: is it socially irresponsible?” Journal of Business Ethics 124 (1), pp. 173-184.

21. Dowling (2014), op. cit., footnote 20.