Prices of innovative drugs: a debate that has been cut short

Media release

Paris, October 3, 2016 – In the last few months, the Ligue contre le cancer and Médecins du Monde, together with a group of 110 cancer specialists, have protested against the prices of innovative drugs. This revolt is likely to nurture discussions regarding the next social security financing plan, which has the stated aim of controlling costs.

This approach is superficial, however, just like the latest campaign by Médecins du Monde. It suggests that drug markers act alone in setting prices and assess “the price of life” on our behalf based on their profitability criteria. Hence the organisation’s call in favour of government intervention to lower drug prices.

This approach ignores the fact that drug prices in France are already administered prices, set by public authorities based on their perceptions of the contributions of new molecules and of their development and production costs. While the prices of some drugs may seem high, this is due more to economic, health and regulatory factors.

It is impossible to conclude that these administered prices are “indecent” and that there is necessarily significant room for manoeuvre to lower them in the short term, except by running the risk of hindering pharmaceutical innovation. Similarly, it is impossible to conclude that more regulation would generate greater savings – quite the contrary. A more competitive organisation of the health system could provide opportunities for improvement.

Innovative drugs: regulated prices

In France, bringing a drug to market involves a long regulatory process, with markers set by public authorities that administer market access approval as well as a drug’s reimbursement and price. Whether by any of several regulatory agencies (ANSM, UNCAM or CEPS), the price is subject to constant control by public authorities. Moreover, regulations force drug makers to finance a portion of health insurance deficits in case of unexpected excess sales of their drugs.

Long and risky development

Price regulation cannot be arbitrary, however, and is based on the industry’s specifics. This is an industry marked by strong R&D needs that are risky by their very nature. R&D investment stretches over a long period – 12 years on average between discovery of a molecule and its commercialisation – and the failure rate is high – only one molecule out of each 10,000 that are screened will make it to market. As such, only 14% to 20% of the innovative drugs that are commercialised will be profitable, and these few must cover all of the industry’s failures, without which future innovation would be impossible.

Declining returns

To this is added the fact that pathologies not yet treated are by definition the most complex, requiring greater R&D investment to discover a treatment. Since 2008, R&D investment by the biggest drug markets has risen 22%, while the number of drugs commercialised has been stable.

Altogether, the current cost of an innovative drug stands at more than €4 billion.

Moreover, with these drugs targeting an ever smaller number of patients, economic logic means that an increasingly high cost per patient has to be set.

Costly regulation

Beyond economic constraints, the time needed for approval and uncertainty over the terms of reimbursement produce added costs that may explain in part why prices are high.

Two possible approaches

Current price regulation seems flawed and may jeopardise the system’s sustainability, failing to ensure drug innovation with access to new therapies for everyone while also controlling public spending. In this context, another approach is possible, turning to competition in the setting of prices by decentralised players – drug makers and insurers – to ensure that drug prices are as low as possible given the sector’s economic constraints.

According to the study’s author, Pierre Bentata, there are probably two approaches to prices: the one taken by the public authorities aimed at continuously regulating imperfect price-setting procedures, and the other turning to true competition in setting prices, relying on decentralised players. The latter approach is clearly the more promising, though it would mark a break with current practice

The study “Innovative drugs: are prices too high?”, is available on our website.

* * *

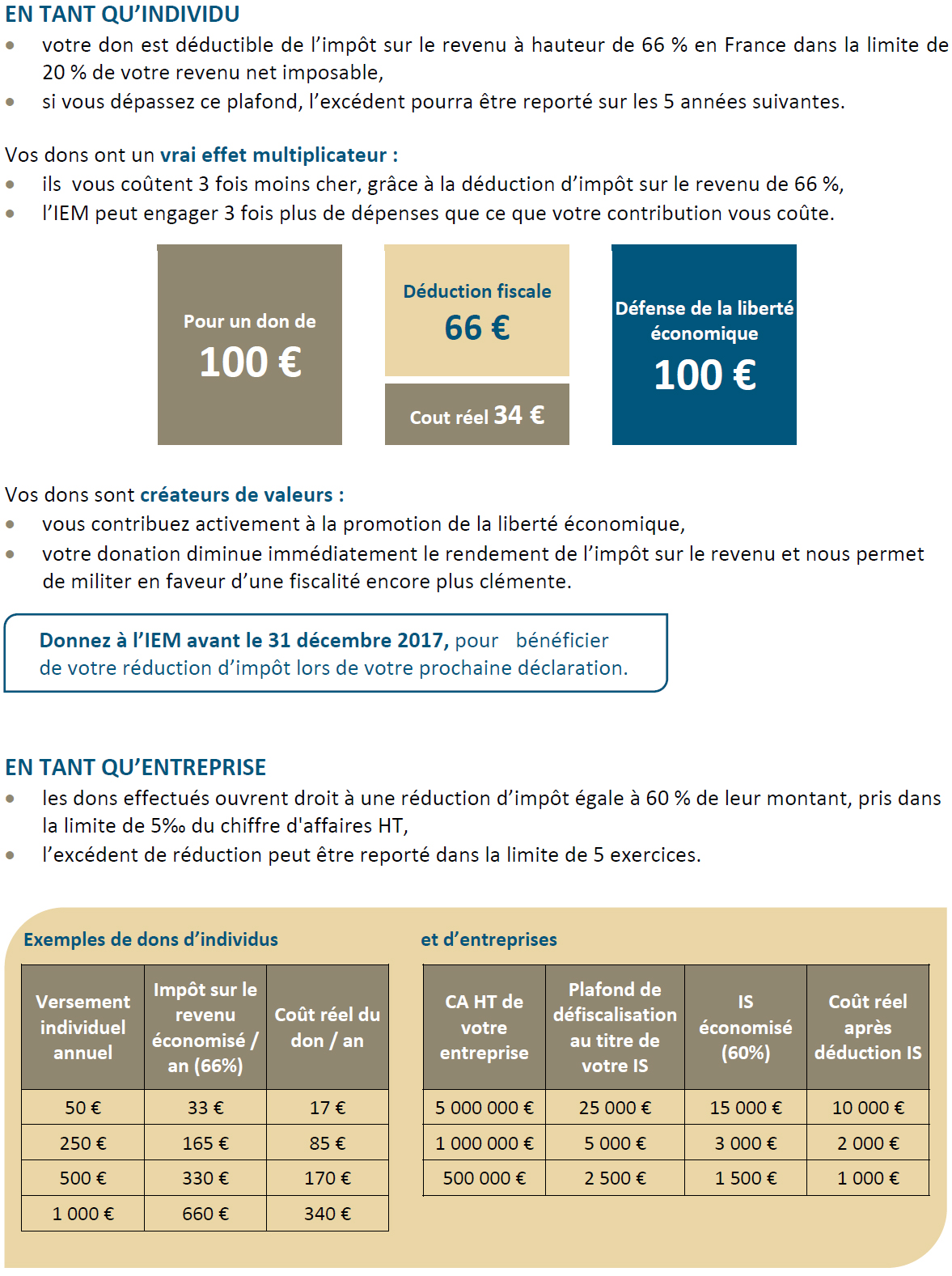

The Institut économique Molinari (IEM) is an independent, non-profit research and educational organization. Its mission is to promote an economic approach to the study of public policy issues by offering innovative solutions that foster prosperity for all.

-30-

Information and interview requests:

Cécile Philippe, PhD

Director, Institut économique Molinari

cecile@institutmolinari.org

+33 6 78 86 98 58